4 Outcome 1.1 NZ history of adult literacy and numeracy

Describe adult literacy and numeracy in Aotearoa New Zealand in relation to the training or education programme

Description includes an outline of adult literacy and numeracy to the present.

Range: outline includes but is not limited to Maori literacy and numeracy pre-colonisation, Maori literacy and numeracy initiatives, issues post-colonisation, literacy and numeracy issues, initiatives for learners from other cultures.

I begin by asking whether it is actually useful to describe (albeit as an outline) the whole history of adult literacy and numeracy in New Zealand. That seems like overkill to me. Will this aid me as a teacher to embed literacy and numeracy in my ESOL classroom? I doubt it. Additionally, I have another couple of issues with that: clarity and relevance.

Clarity

The brief is not clear. Does 'Maori literacy' refer to Maori people learning the Maori language? Or is it Maori people learning the English language? (Or even Non-Maori learning Maori?) If so then this a question of chalk and cheese, apples and oranges. Does adult literacy refer to adults learning a language (either Maori or English) when they are already adult (in which case virtually no history exists!), or does it refer to when they were children on their way to adulthood? Furthermore, is it is mono- or bilingualism that we are to address? Lacking clarity, I feel that it is best to examine the history of foreign-language learning and to derive universal language'-learning principles that apply to everyone in Aotearoa New Zealand, whether they are children or adult, Maori or non-Maori.

Relevance

I have taught ESOL at Otago Polytechnic since 1997 - over 20 years. In all that time I've worked with over 1000 students from about 30 different countries. To the best of my knowledge, not a single one of them identified as being Maori.

Finding myself in such a quandary, I decided to gain clarity and reach relevance by reading a 'clear' and 'relevant' narrative (see John Michael Greer on the power of narrative). Therefore, I selected an autobiographical account written during the period in question, by a writer who experienced the Maori/English bilingual clash first hand.

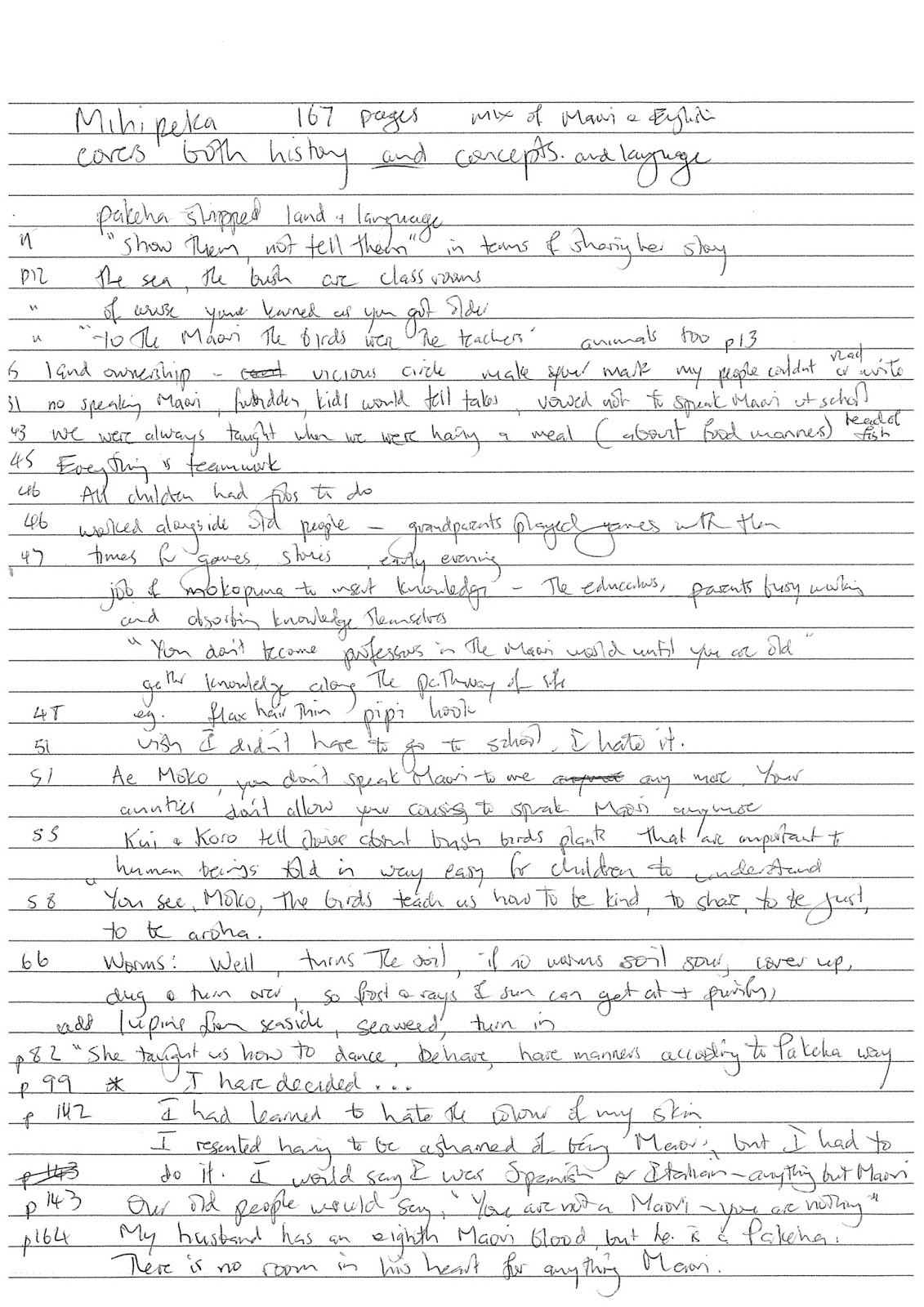

To that end I read and now refer to Mihipeka: the early years. For me, this autobiography written in a mix of English and Maori provides the context that I need to understand what the conditions were in New Zealand in the early 1900s that led to the loss of Maori literacy. It provides all the Maori history, Maori concepts and Maori language that I need.

Notes taken:

Mihi Edwards writes (p99)

I have decided I am going to disown being a Maori. I do not like to be called black nigger and stinky. I have to dodge that somehow. I do not like to be so poor. My Kuia always said I can't be a rangatira if I don't spe3ak my language, but I have decided not to speak Maori any more. It is too difficult to be Maori . . . I am having a terrible time . . . but I have not yet decided what I will be. Maybe Spanish. Or I must learn to use face powder to make myself white like a Pakeha. . . . I do not want to have brown babies.This, to me, points out that there are huge issues that I can only touch on in this rant. There was/is obviously a huge tension between wanting to be thought of as literate in English, yet wanting/needing to retain a cultural identity through speaking Maori.

Since Maori was predominantly a spoken language (although it had been captured on paper since 18.., and as late as 1913 ..% of all Maori could write their own language using 'romaji' alphabetical equivalents) it is likely that the Maori language wasn't respected in a literate sense by Europeans as much as their own tongues. It mightn't have seemed a 'proper' language to them.

To some degree I can relate to this second-class classification, since my parents are immigrants to this country, arriving from The Netherlands in the 1950s. They are close to being from the same generation as Mihi Edwards. My mother at the age of 90 still tells stories of being admonished for speaking Dutch with am countrywoman on the bus and to "Use the Queen's English", and for being advised that at the bridge club that her English was very good (after residing in New Zealand for more than 30 years) but that it could be much better.

The unit standard asks us to go into the history of adult literacy in Aotearoa. I don't consider that useful or relevant. Rather, I would recommend that ESOL teachers make themselves more aware of the history behind foreign-language teaching.

Kato Lomb's book, Polyglot: How I learn languages provides some interesting information on that. Chapter 6 is particularly relevant.

Foreign language learning started with the Romans and Greeks. By learning both languages your status grew. Then, Latin and Greek were taught as classical languages in English schools. They were a disciple. The languages were to all intents and purposes dead. Because of their economic power, the English way of teaching and learning languages became the norm. It has never outgrown its pedagogical heritage. Languages were never learned as a part of real life. They were divorced from the real world.

Comments

Post a Comment